Quick answer: How many watts does an air conditioner use?

A typical central air conditioner commonly draws about 3,000-3,500 watts while the compressor is running. A typical window air conditioner uses roughly 1,000-1,500 watts. Exact wattage depends on unit size (BTU or tons), efficiency rating (SEER, EER, SEER2), age and technology, plus home characteristics and climate.

Why it matters: knowing watts translates runtime into kWh and dollars, helps compare equipment, and is essential for generator or solar planning. For example, a central AC that consumes around 2,500 kWh per year costs about $437.50 at $0.175 per kWh. Since air conditioning accounts for roughly 19% of U.S. home energy use, small watt differences add up over a season.

Use these headline numbers as a quick yardstick, then adjust based on capacity and efficiency. Larger, older, or lower efficiency systems tend to run higher, while smaller or higher efficiency models run lower, especially in mild weather or well insulated homes.

How AC power is measured: watts, kilowatts and kWh (and how to read nameplate numbers)

Watts are power, the instant rate of electricity use. Kilowatts are thousands of watts. Kilowatt-hours are energy, the total used over time, like miles driven versus speed.

In the field, we read an A/C nameplate and estimate running power as watts ≈ volts x amps. That gives the rate when the compressor is on. Because systems cycle, average hourly power is often lower, commonly around two-thirds of the running watts.

- Find watts from the label or use volts x amps.

- Convert to energy: kWh = (watts/1,000) x hours of operation.

- Scale to days, months, or a cooling season.

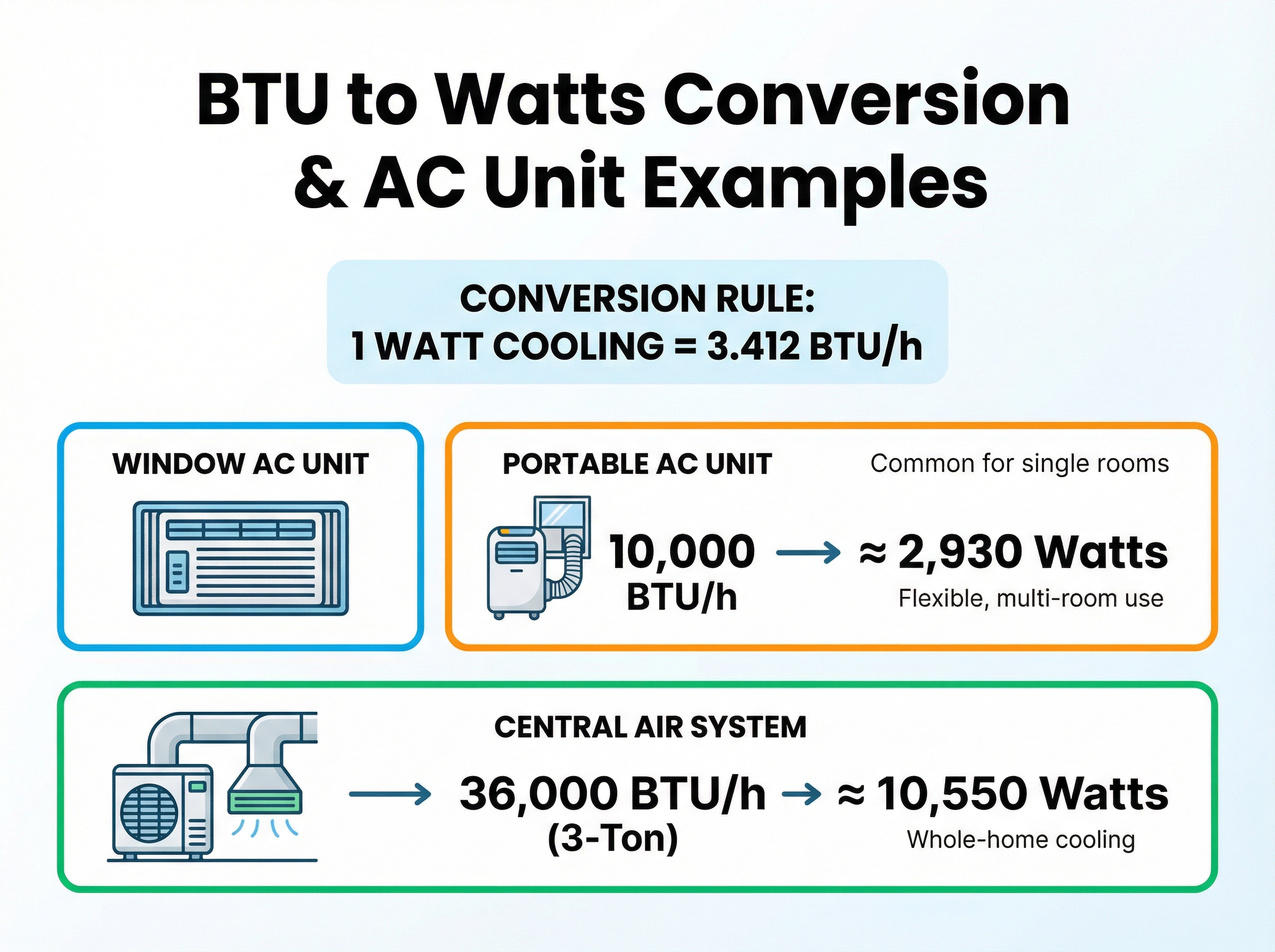

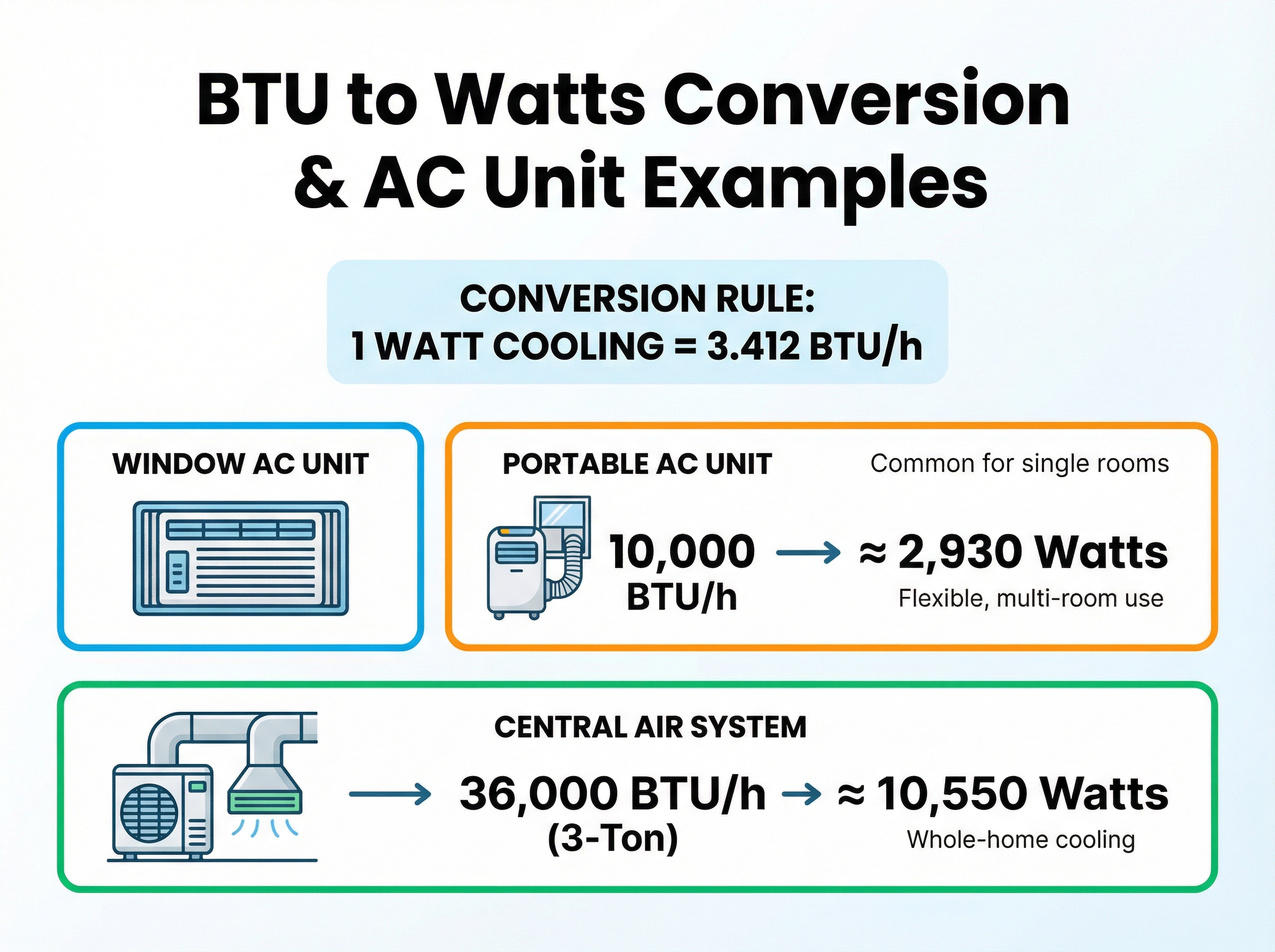

BTU to watts conversion (and what 1,500 watts of cooling equals in BTU)

Cooling capacity and electrical power are easy to translate. One watt of cooling equals 3.412 BTU/h, so multiply watts by 3.412 to get BTU/h, or divide BTU/h by 3.412 to get watts of cooling. If you simply convert 1,500 watts, it equals about 5,118 BTU/h of cooling before accounting for efficiency. In real equipment, not every electrical watt becomes cooling. To estimate electrical input from a rated capacity, use the efficiency ratio: electrical watts ≈ BTU/h ÷ SEER for seasonal use, or ÷ EER for steady state. This ties nameplate capacity to expected power draw.

Wattage examples: 8,000 BTU, 12,000 BTU (1 ton), 2 ton and 5 ton units (real calculations)

Here are real running watt examples using the straightforward BTU ÷ SEER shortcut and the field tested 1,000 W per ton rule of thumb we use when sizing power needs.

- 8,000 BTU room unit at 15 SEER: 8,000 ÷ 15 ≈ 533 W running.

- 12,000 BTU (1 ton) at 15 SEER: 12,000 ÷ 15 ≈ 800 W. If it runs 8 hours per day, that is about 6.4 kWh per day.

- 2 ton split system: about 2,000 W using the ~1,000 W per ton rule (compressor only, excludes the indoor blower).

- 5 ton split system: about 5,000 W using the same rule of thumb (compressor only).

- How SEER changes watts on a comparable 3 ton: roughly 2,571 W at 14 SEER, ~2,250 W at 16 SEER, ~2,000 W at 18 SEER, and ~1,636 W at 20 SEER. This shows why higher SEER trims running watts.

These quick checks line up with what we see in the field and keep planning simple without overcomplicating the math.

When watt estimates and common rules break down: tradeoffs, mistakes and better alternatives

From decades in the field, we see the same shortcuts waste power and comfort. Quick hits that matter:

- Myth: closing vents saves energy. Reality: it raises static pressure, increases blower watts, worsens duct leakage. Use zoning instead.

- Myth: leaving AC on all day is cheaper. Reality: total energy follows runtime, sensible setbacks usually save.

- Myth: fan only is free. Reality: blowers draw real watts, auto fan or efficient ECM motors reduce waste.

- Myth: dirty filters and coils barely matter. Reality: they spike blower and compressor load, maintain them.

- Myth: bigger units cool better. Reality: oversizing short cycles and dehumidifies poorly. Insist on a Manual J load.

- Myth: lower thermostat cools faster. Reality: it just runs longer and uses more energy.

- Myth: add refrigerant yearly. Reality: low charge means a leak, fix the leak.

- Myth: high SEER always means low watts. Reality: check EER or EER2 for peak conditions and get the ducts right.

Avoid sizing by BTU per square foot only. Factor climate, insulation, windows and occupancy, then select equipment from a proper Manual J.

- Extreme cold: a cold climate heat pump or a gas furnace is often the better fit.

- Uneven multi room homes: true zoning beats closing vents.

- Very hot regions: prioritize strong EER or EER2 over chasing SEER alone.

Typical wattage by AC type and size: window, portable, ductless and central systems

Here is a quick way to place your AC on the power spectrum. In our experience at Budget Heating (BudgetHeating.com), these are the typical draws we see on nameplates and power meters.

- Window AC: Many models use roughly 1,000 to 1,500 W. Very small room units can be about 500 W. Larger window units near 12,000 to 14,000 BTU often land around 1,200 to 1,500 W.

- Portable AC: Many fall around 900 to 1,800 W. As a single room option, portables and window units together broadly sit in the 500 to 1,500 W range depending on BTU and efficiency.

- Ductless mini split: Individual indoor heads are commonly about 600 to 3,000 W each at full output, depending on size.

- Central split or package system: Typical running draw is about 1,500 to 5,000 plus W for the outdoor unit when the compressor is on.

Simple sizing rule of thumb: about 1,000 W per ton of cooling. One ton is roughly 12,000 BTU per hour. For example, a 3.5 ton system may pull about 3,500 W when the compressor runs. Think of tonnage like engine size and watts like fuel used at full throttle.

Do not forget the blower. In fan only mode, a central system still uses power. Older blowers can draw around 750 W, while ECM motors typically use less.

Use the ranges above to sanity check a label or an energy monitor. Efficiency, outdoor temperature, and part load can move the actual number, but if you know your unit's BTU or tonnage, these ballpark figures will get you very close.

How SEER (and SEER2) and efficiency affect AC power consumption

SEER is the Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio, the seasonal BTU of cooling delivered per watt-hour. SEER2 is the 2023 update that reflects real ducted-system conditions. As a rule, running watts ≈ BTU ÷ SEER, so higher SEER means fewer watts for the same cooling.

Typical ranges: older units 8-10 SEER, modern baselines 14-15, high-efficiency 18-25+. Savings scale quickly: 14→18 SEER trims running watts about 22 percent, 14→20 about 30 percent, and 10→16 can cut cooling energy roughly 38 percent.

Since 2023 the U.S. sets federal minimums using SEER2/EER2/HSPF2, with higher regional minimums in hot southern zones and ENERGY STAR tiers above that. In hotter climates new systems start at higher required efficiency, lowering watts per BTU delivered. In our experience at Budget Heating (BudgetHeating.com), SEER2 ratings make comparisons more realistic.

Portable and RV air conditioners: typical watt draw and sizing notes

From our field work, we size portables and RV units by square footage and sun load, then check watt draw. Most portable ACs pull about 900 to 1,800 W while cooling. Larger portables can push into the upper thousands depending on BTU and efficiency. For renters, start with about 20 BTU per square foot and adjust for high ceilings, lots of glass, or strong sun.

RVs and manufactured or mobile homes follow the same math. Smaller manufactured units often need about 12,000 to 18,000 BTU, with watts scaling to the BTU and the unit's efficiency. Use the standard BTU to watt relation to estimate load, then be sure your branch circuit, shore power, or generator has headroom for steady running plus brief compressor startup.

How to calculate watts per hour, estimate monthly cost, and what changes real world power draw

To translate watts into a bill: Energy (kWh) = watts ÷ 1,000 × hours. A 3,000 W central unit for 1 hour uses 3 kWh. At $0.175/kWh, 3.0-3.5 kW costs about $0.53-$0.61 per hour. If it runs 6 hours a day, that is 18-21 kWh/day or $3.15-$3.68, and about 540-630 kWh/month, roughly $94-$110.

Example at the room scale: a 12,000 BTU/h window unit at 15 SEER is about 800 W. At 8 hours/day it uses ~6.4 kWh/day, near $1.12/day or ~$34/month.

In our field work, actual draw depends on: capacity, efficiency rating, climate and duty cycle, envelope and duct losses, thermostat settings and controls. Condensing units often cycle 2-3 times per hour for 15-20 minutes, so power is only used while running. Annual cooling varies by climate: hot humid ~4,000-6,000 kWh, hot dry ~3,500-5,500, moderate ~1,500-3,000, cool ~500-1,500. Upgrading efficiency can cut use by roughly 20-50 percent.

Conclusion: estimate your AC watts, check your bill, and consider efficiency upgrades

Bottom line: estimate your AC's watts from the nameplate or a calculator, compare it to your utility kWh, then decide if maintenance, sizing or an upgrade will move the needle. Remember, compressors can pull 2 to 3 times their running watts at startup due to inrush current, which matters for generator or inverter sizing.

Keep watt draw in check with simple care: replace or clean filters every 1 to 3 months, keep supply vents and the outdoor unit clear, and confirm thermostat schedules. Leave refrigerant work, deep coil cleaning and electrical diagnostics to a licensed tech. Call a pro if you see breaker trips, burning smells, icing, short cycling, sudden performance loss, refrigerant issues or post storm damage. If numbers still look high, consider higher SEER2 equipment, correct sizing with Manual J, smart thermostats, better insulation and shading, and clean ducts and coils.

- Get a Custom Quote for right sized, high efficiency systems

- Talk to Our Team, U.S. based phone support with real HVAC techs

- Shop AC and Heat Pumps at wholesale pricing, many items ship free, financing available with Affirm