Do Central Air Conditioners Use Water? The short answer

No. Central air conditioners in typical homes do not use water to cool. They circulate a closed-loop refrigerant that absorbs heat from indoor air at the evaporator coil and rejects that heat outdoors at the condenser. If you notice water around the system, it is not part of the cooling method, it is a byproduct.

Here is what that water is: as warm indoor air moves across the cold evaporator coil, moisture in the air condenses on the coil surface, like a cold glass sweating on a summer day. That liquid is called condensate. By design, it collects in a drain pan and is routed out through a condensate drain line to a suitable discharge point. In humid weather, a steady trickle from that line is normal.

Bottom line, a central AC cools with refrigerant, not water. Any water you see should be limited to the condensate system, and it should be properly captured in the drain pan and carried away through the drain line. Water appearing elsewhere signals a drainage issue, not that the unit uses water to operate.

How central air conditioning actually works: the refrigerant cycle (not water)

Most central systems use an air cooled vapor compression loop that stays sealed from end to end. The core parts are the compressor, the outdoor condenser coil and fan, an expansion device, and the indoor evaporator coil. Think of the refrigerant as a moving conveyor for heat: it carries heat out of the house, then gets ready to pick up more.

Here is the cycle in plain terms. The compressor squeezes refrigerant vapor to a high pressure and temperature, so it can give up heat outdoors. In the condenser, outdoor air passes over the coil, the refrigerant releases heat and condenses to a high pressure liquid. That liquid is metered through an expansion device, which drops its pressure and temperature. Now cold and low pressure, the refrigerant flows through the indoor evaporator coil. The blower pushes room air over this coil, the refrigerant absorbs heat and boils back to vapor, and the air leaving the coil is cooler and drier. The vapor returns to the compressor and the loop repeats.

Heat is absorbed at the indoor coil and rejected at the outdoor coil, so the system circulates refrigerant and electricity, not a continuous supply of water. Any water you see is simply a byproduct of dehumidification.

Why is water dripping from my central AC? Common causes of condensate leaks

Seeing water by your central AC can be confusing. Around the air handler, it almost always points to a drainage issue, not that the system uses your household water. Condensate should leave through the drain line, so any pooling at the unit means something is off.

- Clogged condensate line: Algae or slime can narrow the pipe and back water up into the unit.

- Rusted or cracked drain pan: Corrosion or a hairline crack lets water escape before it reaches the drain.

- Missing or damaged P-trap: Without a proper trap, airflow can disrupt drainage and cause intermittent overflow.

- Frozen evaporator coil: Ice forms during operation, then thaws and overwhelms the pan and drain.

How to tell normal from a problem: a dry area around the air handler is expected, while puddles or stains around the indoor unit signal a blockage or failed part. After heavy runtime, thawing frost can drip for a while. Persistent moisture points to a drainage fault that needs fixing.

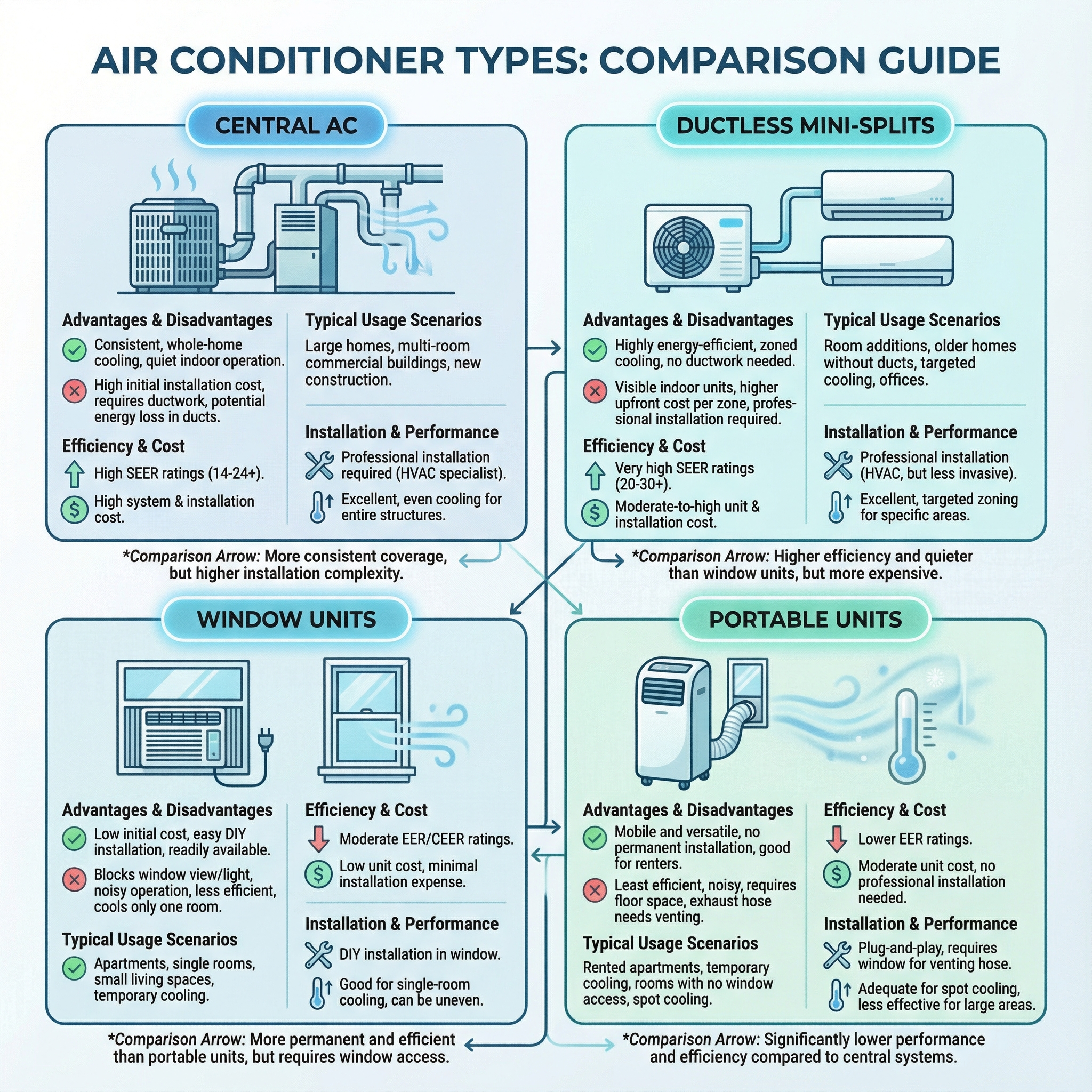

What is a closed loop chilled water system and how is it different from home central AC?

A closed loop chilled water system cools water at a central plant, then circulates that chilled water through insulated piping to air handlers or fan coil units throughout the building. As room air passes across each coil, heat is absorbed by the water and carried back to the plant to be cooled again. The unwanted heat is then rejected at a central cooling tower or condenser plant. In other words, the building uses water as the transport medium, not long runs of refrigerant. We see this daily in larger facilities where pumps, headers, and control valves tie many zones into one loop.

That is different from typical home central AC, where a refrigerant based split system is the norm. Single family houses almost always use air cooled outdoor units with a small refrigerant lineset to an indoor coil, not a chilled water and cooling tower infrastructure.

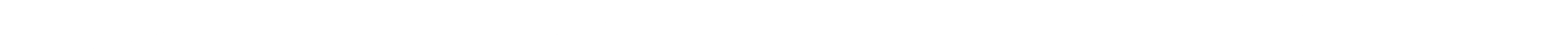

Maintenance & safety: how to prevent water problems and when to call a professional

Start with airflow. Replace air filters every 1-3 months, keep return and supply grilles clear, and have the evaporator coil cleaned when buildup prevents air from contacting the cold coil surface, since that contact drives dehumidification.

Outside, keep 2-3 feet of clearance around the condenser. Cut power at the thermostat and the outdoor disconnect, then gently rinse the coil with a garden hose. Never use a pressure washer. We do not open sealed refrigerant circuits at home, and we do not probe high-voltage parts. Refrigerant handling requires EPA 608 certification, and capacitors can hold a dangerous charge even with power off.

- Repeated drain clogs or water near electrical components

- Frequent short cycling or ice on the evaporator

- Indoor relative humidity above about 55% despite long runtimes

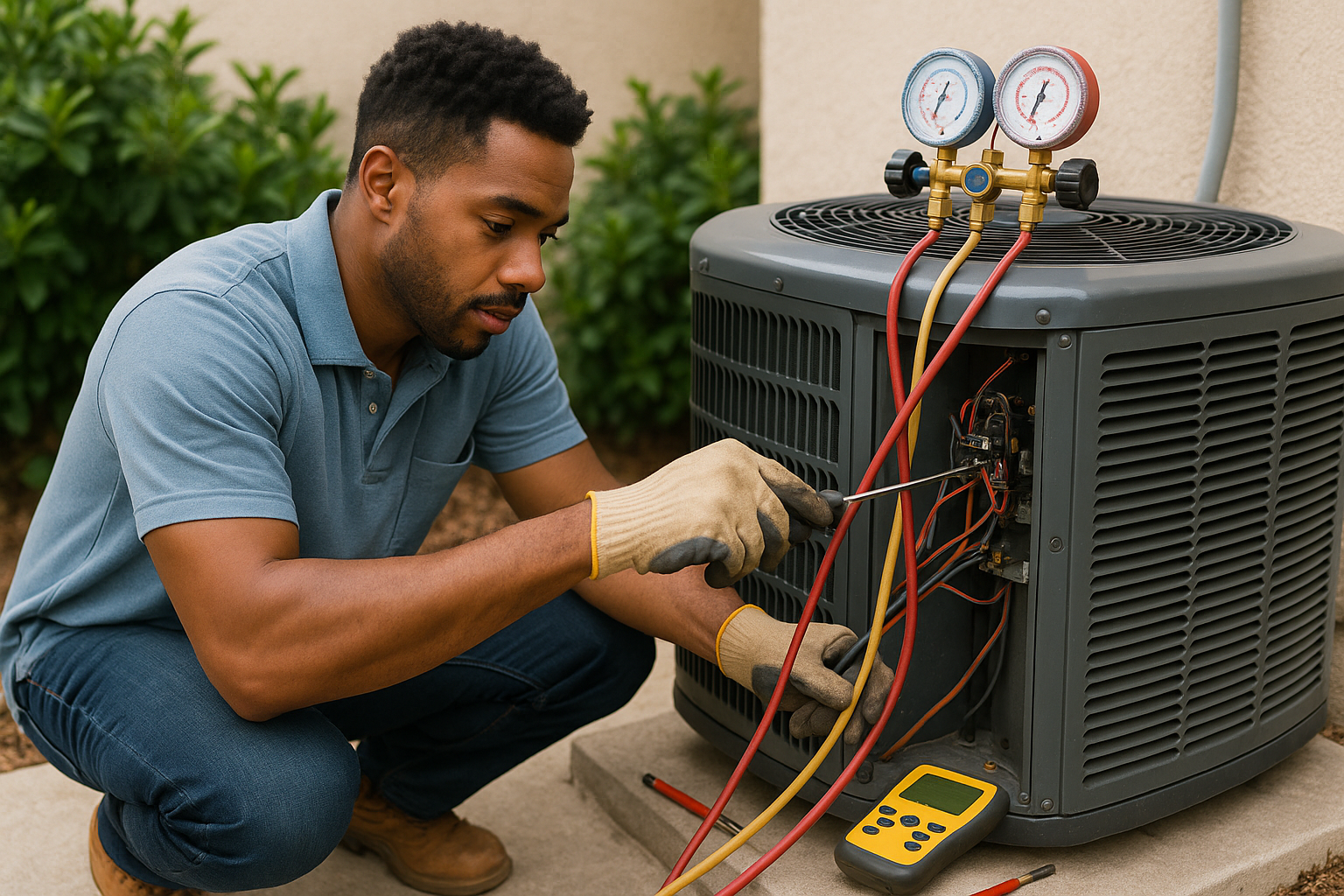

Air cooled vs water cooled systems and evaporative coolers: which ones actually use water?

Air-cooled central AC rejects heat directly to outdoor air using a condenser coil and fan, so it does not consume water. Water-cooled condensers move heat into a building water loop that sends it to a cooling tower, which evaporates water to shed heat. These setups appear in larger buildings and industrial sites where a loop and tower already exist, and they require a reliable water supply and ongoing tower maintenance, including water treatment.

Evaporative coolers, often called swamp coolers, deliberately consume water and add humidity. They work best in hot, dry climates, not in humid regions. Some rooftop units also use evaporative pre-cooling on the intake air to boost efficiency on peak days.

Which systems actually use water: evaporative coolers, rooftop units with evaporative pre-cooling, and large commercial water-cooled or chilled-water plants paired with cooling towers. These are distinct from typical single-family central AC.

- If your climate is humid, evaporative cooling is a poor fit. An air-cooled heat pump or high-efficiency split AC is a better choice.

- If water is scarce or costly to manage, avoid towers and evaporative gear. Choose air-cooled packaged or split systems.

- If you lack tower infrastructure, small buildings and homes should stay with air-cooled systems rather than water-cooled condensers.

How much water does a central AC actually use? Typical condensate amounts and factors

Central AC systems do not use water to operate. Standard residential units are air cooled, so there is no ongoing water usage cost tied to cooling. The water at the drain is condensate from indoor air, not from a metered supply, so it does not raise a typical water bill. Your operating cost is electricity, not water.

How much ends up in the drain depends on conditions. In humid climates the process can remove several gallons per day. The total varies with climate, runtime, and indoor humidity:

- Climate humidity: wetter outdoor air leads to more moisture removed.

- Runtime: longer daily run time means more condensate collected.

- Indoor humidity: aiming for drier indoor air increases the amount removed.

Condensate management: drains, P traps, condensate pumps and emergency pans

The P-trap holds a water seal, like a sink trap, to block air and help drainage.

- Locate the indoor unit’s primary drain line, trap and pan. Ensure the line slopes to its outlet, the trap is intact, and the discharge point is clear.

- In attics or upper-floor closets, verify a clean secondary pan and a working float switch.

- At the start and mid season, flush the drain with a cup of distilled vinegar, then use a wet/dry vacuum at the outside outlet to clear algae. At Budget Heating (BudgetHeating.com), this simple routine prevents most clogs.

- If a condensate pump is installed, clean the reservoir and inlet screen, then pour water to confirm the pump cycles and the safety switch works.

- Call a pro if the trap is missing or cracked, the pan is rusted or still wet after a flush, the line lacks slope, or no secondary pan is present.

When to replace the condenser and how efficiency (SEER/SEER2) affects operating cost

SEER and the newer SEER2 measure seasonal cooling output divided by electricity used, higher numbers mean less energy for the same cooling. Since 2023 the U.S. uses SEER2 and EER2 with region specific minimums. Think of SEER like miles per gallon for AC.

Replace the condenser when comfort or cost say so: if it cannot control humidity, its sensible heat ratio and single speed do not match your climate, or bills are high. Upgrading from SEER 10 to SEER 16 on an 18,000 BTU system in Florida can drop annual cooling cost from about $588 to $367, roughly 37.6 percent.

Avoid a common mistake: choosing or rejecting systems based on whether they use water. Decide by capacity, efficiency, humidity control, and installation quality. In our experience at Budget Heating (BudgetHeating.com), matching capacity, sensible heat ratio, and variable speed to your climate yields the best comfort per dollar.

Bottom line: Central ACs don’t use household water, manage condensate and choose by efficiency

Most central ACs are air cooled and use refrigerant, not household water. The water you see is normal condensate that should drain away. Keep the drain line and pan clear, schedule seasonal tune ups, verify proper sizing, and when replacing, compare SEER2 ratings to trim electricity use by 10 to 25 percent.

Deciding between repair and replacement is a big call. With 30 plus years in HVAC and over 200,000 orders fulfilled, our team can size, price, and ship the right setup with full factory warranties.

- Get a Custom Quote for right sized, high efficiency equipment

- Talk to Our Team by phone for drainage tips or replacement guidance, U.S. based tech support

- Shop Central ACs at wholesale pricing, many with free shipping and Affirm financing